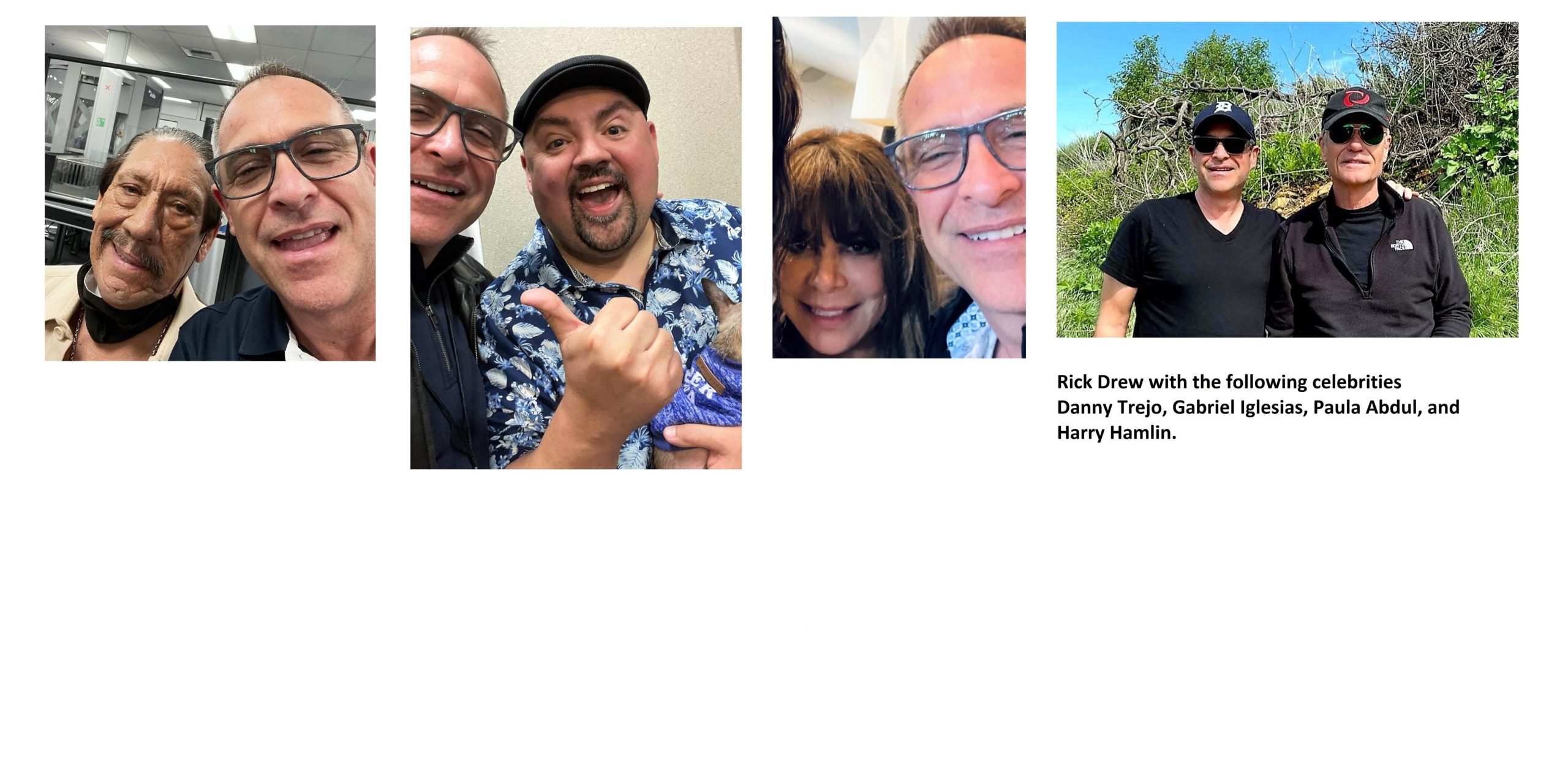

My charismatic brother, Rick Drew, has an uncanny ability to meet celebrities. In the collage above you can see him in photos with Danny Trejo, Gabriel Iglesias, Paula Abdul, and Harry Hamline. He is a master networker who charms the stars with his intelligence, good looks, and affable personality.

In a similar fashion, successful grant writers are usually masters of leveraging the strengths of their personal network. This is because success in grant writing goes to those folks who manage to pull together a lot of information quickly and produce a conforming document under the pressure of a tight deadline. The only way to do that is to work effectively with the people around you. After all, the grant writer is dependent on the accounting office for budget information, the executive director’s office for goals and vision, the program administrators for day-to-day expertise, the clients for practical insight, the staff members for fresh versions of their resumes, and even the funder’s own administrators regarding the details of the application.

Somehow, the best grant writers have a knack for managing small, temporary workgroups. One of my secrets to success is to pay attention to the temperaments of the people involved in the process.

In Lao Tzu’s book, The Art of War, he writes there is a place for everybody when you are planning a military campaign. He says that those who are impulsive and full of courage should be given the honor of leading the charge. Those who are naturally cautious and careful are better employed in logistics and planning. The challenge is to size up your group and make intelligent assignments.

At the start of the grant writing process, I like to leverage the excitement and enthusiasm of the most outspoken proponents of the grant. I encourage them by rapidly creating a complete A-Z grant application that puts their biggest and best ideas into a rational, conforming framework. I encourage them to shoot for the stars, apply the latest research, and compile their most inspirational wish list.

As I near completion of the project, however, I like to encourage the voices of the project pessimists, the ones who may have been indifferent, or actively opposed, to writing the grant in the first place. Frequently, I have found that those who were most resistant to even trying for the grant can be quite helpful in polishing up and perfecting it at the end of the process. I like to leverage the naysayers by encouraging their criticism, asking for their harshest observations, and implementing their most realistic perspectives.

One of the advantages of this approach, by the way, is that the most aggressive grant optimists have, in all probability, lost interest in the project and are moving on to fresh endeavors.

Accordingly, I think it is important to stress that grant writing is more of a team sport than a form of solitary contemplation. There is a lot of money to be made by paying attention to your team’s personalities, strengths, and weaknesses. There is a lot of money in making the best use of the people you meet.